“The market is ridiculously overcrowded with early-stage investors. A lot of these early-stage investors will fund literally anything… [it’s] the assembly line approach to investing.”

What’s the problem with that? Supposedly this helps entrepreneurship thrive, but in his opinion, this results in a talent drain – the best talent goes off to work on a small startup because they can get funding, but their skills would have been better put to use in a larger company, with more impact. Israeli VC Michael Eisenberg agrees with Parker in principle.

This week, I was talking to Ivan Farneti of Doughty Hanson, a UK VC/PE fund. I asked him what does he think about the recent talk in the industry about over funding, and the fact that incubators like 500Startups managed to invest $13 million in 186 companies over the course of 18 months…

Ivan’s thoughtful response sounded like it was taken out of the Godfather movie, so I had to share it here: there are games of skill and games of luck. If you have a serial entrepreneur with a couple of successful companies under his belt, we’re talking skill (on the part of the entrepreneur). For all the others, much of their failure or success is down to luck. He added that in the incubator model, a lot of it is down to luck and most funds have one massive exit that cover for all their other ‘f-ups’. Be it Google, Amazon, Facebook, LinkedIn, Skype, Bebo, Twitter, etc – most of the top funds have one (or more if they’re really lucky) of these companies.

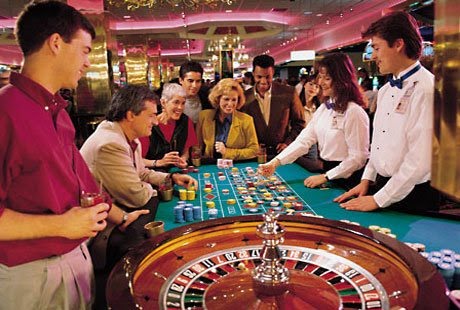

This got me thinking – In the roulette table, the odds are set. If you bet on a single number and win, you get 36 times your money. In early stage startup investing, the return could be much higher than that. The strategy is simple – spray and pray. Cover as many numbers in the roulette table (if you can afford it), try to improve your chances by giving the startups (free) mentorship and setting up a (loose) screening process… and hope for the best.

Traditional VC seemed to be more strategic. Pick a sector, do your research, select the potential winners, conduct strict due diligence and hope you picked the winner. Not quite the spray and pray that we see with angels and accelerators, but which strategy is more successful?

Earlier this month, Business Insider’s chart of the day showed how this looks in practice:

We’ve all heard this a million times. The cost of starting a technology business have gone down dramatically. Technologies like the cloud and open platforms, enable developers to build products with a few thousand dollars without the need to spend millions on servers or maketing. Accelerators take advantage of the rising tide, offering entrepreneurs something they need more than money – advice and a sense of community (sure, some money as well).

The alternatives for funding are many and the barriers to reach investors have reduced significantly. Crowdfunding is getting more popular, any startup can set up a profile on Angel List and reach a community of qualified investors and advisors. Kickstarter, while mostly targeted at funding art projects, is also getting a lot of traction, and some entrepreneurs list their companies on the site for both funding and marketing. There’s more accelerators than ever before, some offering as much as $150,000 to any startup that gets in (TechStars and Ycombinator are too examples). Regional incubators and accelerators are also thriving and startups can find at least one in every country these days. Most universities also have programs to support entrepreneurs.

So what does this all mean? there’s more early stage investors, there’s more organized access to early stage investors, it’s cheaper to start a business and there’s more small businesses than ever. Is there a talent drain? Or is the experience of starting a business valuable for everyone? presumably not all these two-person companies last for ever. The founder end up getting acquired or quit to go into big companies, bringing their learnings with them. They teach the next generation of entrepreneurs and form a community. The gap between the big companies will reduce and we will see a more integrated industry.

- Don’t Sleep on Consumer Tech: AI is Changing Everything - March 16, 2025

- Weekly Firgun Newsletter – March 14 2025 - March 14, 2025

- Israeli Pre-Seed Report 2025 - March 12, 2025

Comments are closed.